12 Feb CBRM Councilor Calls for Cape Breton Nominee Program

[vc_row css_animation="" row_type="row" use_row_as_full_screen_section="no" type="full_width" angled_section="no" text_align="left" background_image_as_pattern="without_pattern"][vc_column][vc_column_text]The Cape Breton Spectator | Mary Campbell | November 1, 2017.[/vc_column_text][vc_separator type="normal"][/vc_column][vc_column][vc_column_text] [caption id="attachment_15683" align="alignright" width="225"] CBRM District 8 Councilor Amanda McDougall[/caption]

CBRM District 8 Councilor Amanda McDougall thinks Cape Breton needs its own Nominee Program for immigrants and on October 16th, she shared that opinion with the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Citizenship & Immigration (CIMM).

It was a return engagement for McDougall, who had been deprived of the opportunity to address the same committee in June by one of its members (who shall remain nameless but whose last name rhymes with “temple” and who didn’t actually attend the October 16th session.)

CIMM has been holding meetings (nine to date) and hearing witnesses (55 as of October 19) and collecting briefs (10 in total) in response to M-39, a private member’s motion by Fundy Royal Liberal MP Alaina Lockhart. M-39, which passed unanimously in the House of Commons on 22 November 2016, mandated the committee to study immigration to Atlantic Canada, paying particular attention to:

CBRM District 8 Councilor Amanda McDougall[/caption]

CBRM District 8 Councilor Amanda McDougall thinks Cape Breton needs its own Nominee Program for immigrants and on October 16th, she shared that opinion with the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Citizenship & Immigration (CIMM).

It was a return engagement for McDougall, who had been deprived of the opportunity to address the same committee in June by one of its members (who shall remain nameless but whose last name rhymes with “temple” and who didn’t actually attend the October 16th session.)

CIMM has been holding meetings (nine to date) and hearing witnesses (55 as of October 19) and collecting briefs (10 in total) in response to M-39, a private member’s motion by Fundy Royal Liberal MP Alaina Lockhart. M-39, which passed unanimously in the House of Commons on 22 November 2016, mandated the committee to study immigration to Atlantic Canada, paying particular attention to:

- The challenges associated with an aging population and shrinking population base

- Retention of current residents and the challenges of retaining new immigrants

- Possible recommendations on how to increase immigration to the region

- Analysis of the Atlantic Immigration Pilot initiatives associated with the Atlantic Growth Strategy

- That the Committee report its findings to the House within one year of the adoption of this motion.

What we did was interview the international student population just to get a better grasp on what they were feeling here, what are your barriers? What are your challenges when you’re thinking about becoming a permanent resident. Do you even want to be here? What are the problems that you are seeing in Cape Breton around racism? Around acceptance into communities?The results of their work are contained in this May 2015 report and provided the basis for her recommendations to the committee on the Atlantic Immigration Pilot which, she acknowledged, had encountered problems since it was rolled out in July 2016 with the stated goal of attracting 2,000 skilled workers to Atlantic Canada:

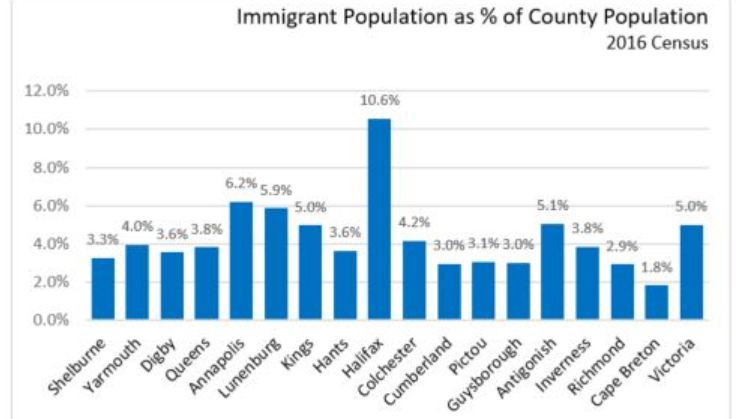

It does stand to be a great program, I think it’s a great idea, [it just] might have been rolled out a little too early, without some public thought process of…how can we make sure this benefits…urban and rural [communities]? Because right now if you’re a…potential newcomer to Canada, specifically to Nova Scotia, and you go on the federal government’s website, it says, “Go to Halifax.” Even if you go to the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration website as well, there is really nothing directing people to other places, it’s very Halifax-centric and that was a lot of what I talked about when I was up in Ottawa.

Face-to-Face

McDougall and her fellow witnesses at the October 16th session were each given seven minutes to present, after which committee members had a chance to ask them questions. You can listen to the entire October 16th session on ParlVu. (Technical note: I found it wouldn’t work for me in Chrome or Mozilla, but did work in Explorer and on my Android phone). If you only have seven minutes, I have helpfully cut everything out of the two-hour session except McDougall’s presentation and posted it below. Don’t say I never did anything for you. (Another technical note: this is an audio-only file despite all appearances to the contrary.)

[video mp4="http://cbvoices.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/McDougall_Committee_Presentation.mp4"][/video]

What McDougall discussed with the committee (and with me last week) was her conviction that one of the biggest problems facing would-be immigrants to Cape Breton is the lack of face-to-face support services, “We heard that from our Syrian families, we heard that from community groups, we heard that from international students.”

It’s a problem she places squarely at the feet of Nova Scotia’s Office of Immigration, which had funded the Rural-Urban Immigration Pilot, and she’s pretty blunt about it: “I have a big beef with the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration.” At the time of the pilot project, she said:

I think the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration was receiving just under $6 million from the federal government to implement services and promotions and marketing for the whole province — $170,000 was coming to the island…So I would be honest about that, “That’s not adequate, you need a proper network here, you need an office here…People who are going through their permanent residency process cannot talk to anybody here.”McDougall says that lack of in-person services extends to something as simple as seeing a doctor for a certificate of health, which people applying for permanent residency status must have. Said McDougall:

There’s no doctor that is allowed to write, “This person is of good health,” on the island. And so, that one doctor that is in Halifax, it can sometimes take up to five and six months just to get an appointment with him. And…when you’re going through the permanent residency process, it’s very time sensitive. If your Visa runs out, you’re done, you’ve got to go home.I asked the NS Office of Immigration to comment on this but as of press time, a spokesperson was still working on it.

Try this at home

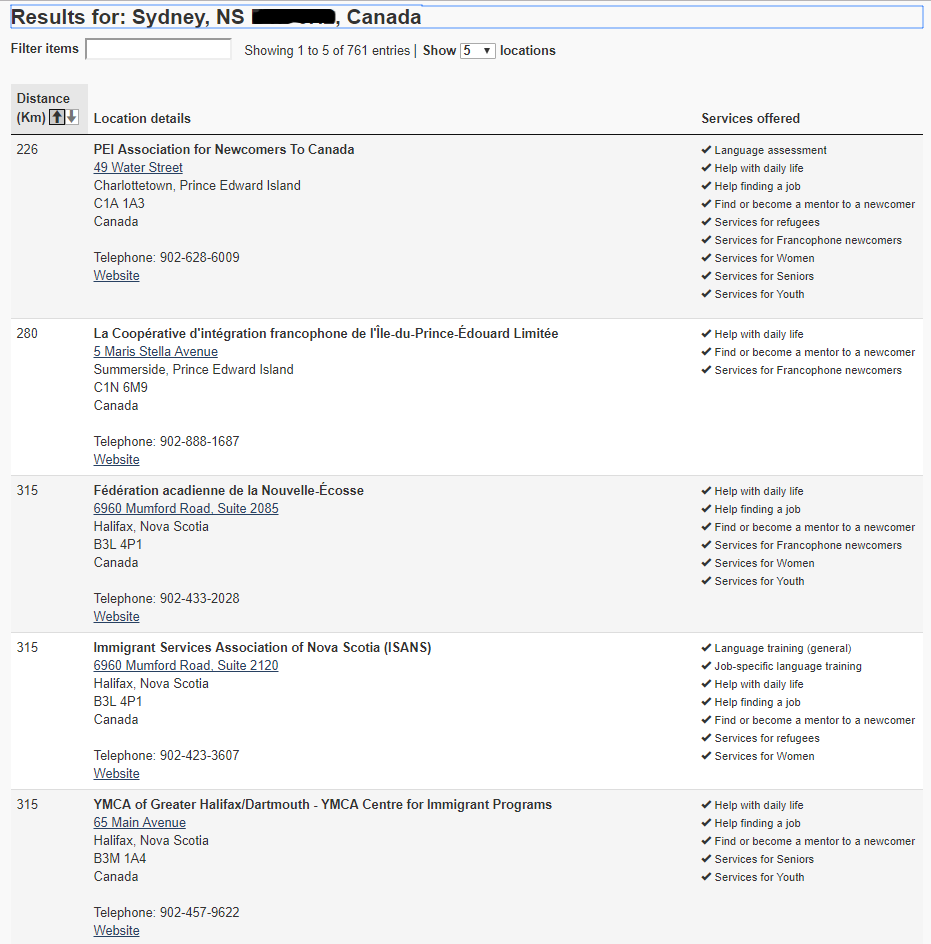

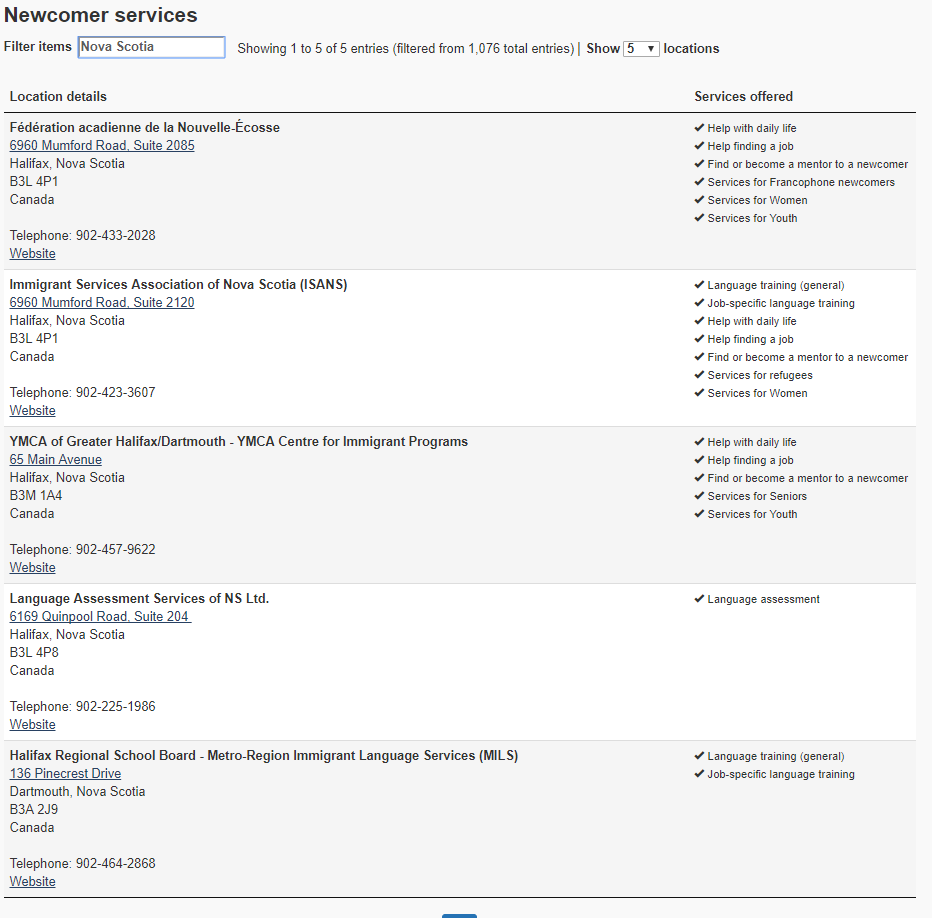

Here’s a completely unscientific but oddly revealing experiment I did on the federal Citizenship and Immigration website to see what kind of support is out there for immigrants in Cape Breton. Under the banner, “Find free newcomer services near you” I typed in my postal code, checked a box next to “help with daily life,” as the service I was looking for and hit “Find.” Here are my results: This is the kind of answer a human would never give you — if I walked into an office in Sydney and asked for assistance with daily life (and there are days I would love to be able to do that), it is unlikely the person I was speaking with would offer me 761 answers, the first five of which involve my either leaving town, leaving the province or learning a second language.

When I filtered the answers for organizations in Nova Scotia (because somehow, my postal code didn’t do that automatically), the 761 answers turned into five, none involving an organization in Cape Breton:

This is the kind of answer a human would never give you — if I walked into an office in Sydney and asked for assistance with daily life (and there are days I would love to be able to do that), it is unlikely the person I was speaking with would offer me 761 answers, the first five of which involve my either leaving town, leaving the province or learning a second language.

When I filtered the answers for organizations in Nova Scotia (because somehow, my postal code didn’t do that automatically), the 761 answers turned into five, none involving an organization in Cape Breton:

I think we’re going to give this round to the humans.

I think we’re going to give this round to the humans.

Audience participation

McDougall said the best part of her appearance was the response from the committee members, both during the session and following it:It kind of made me really think that when people are in these committees they can drop their party colors and talk about the topic. It was great.One interesting exchange was with Marwan Tabbara, the Liberal MP for Kitchener South-Hespeler. Tabbara asked McDougall about the barriers facing international students trying to enter the workforce in Cape Breton and the kind of financial aid they receive from the federal government. When McDougall said there was no federal financial aid, Tabbara asked what kind of financial aid was available from the province, to which McDougall again responded, “Nothing.” [video mp4="http://cbvoices.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Tabarra_Question.mp4"][/video] The answer must have surprised Tabbara, who had prefaced his question by noting that his riding is about an hour away from Toronto and has been “very successful” in attracting international students and workers. It gave McDougall an opportunity to explain that the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration doesn’t see international students as potential immigrants. It’s a subject she returned to in speaking with me last week:

We’re looking at international students like, “Oh, this is such a great opportunity, they want to stay here, their parents are pushing them to stay here, they want to bring their family here, bring their business here.” [But] according to the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration, the programs that they fund, those services, they cannot be utilized by international students because international students are not potential permanent residents, they have an end-date on their visa.To be clear: once an international student has applied for permanent residency, those services do become available to him or her, but McDougall’s point seems to be that there’s an in-between area where some assistance from the Office of Immigration might be all it takes to encourage a student to stay. Again, I asked the NS Office of Immigration about its provision of services to international students, but as of press time, I had not received a reply.

Creative thinking

McDougall said one of her most interesting conversations was with Brandon-Souris MP Larry Maguire, a Conservative member of the standing committee who came up to talk to her following the session. Maguire told her about Manitoba’s approach to immigration which involves allowing communities to nominate immigrants — and making settlement services available throughout the province. In deciding what kind of immigrants to admit, says McDougall, Manitoba:…listened to the particulars, it wasn’t just, “You can have 25,000 highly skilled individuals.” They listened to farmers, they listened to various sectors…You have to listen to the people on the ground. We do have a different type of labor market here, where a lot of it is seasonal, which disqualifies you from the Atlantic Immigration Pilot altogether, but could we not be more creative and say, “Okay, this person could work seasonally with Louisbourg Seafoods, for example, and then go into the tourism sector and do some work?…That’s my whole life. I’ve always held a few jobs and that’s not a bad thing.This 2016 article from the Calgary Herald tells how two small Manitoba towns, Winkler and Morden, used the provincial program to “hand-pick immigrants well-suited for small town life and the needs of local businesses.” (Although I have to admit, the idea of having a municipal bureaucrat playing god in that way sends a slight chill up my spine but that’s a topic outside the scope of today’s article — although maybe not outside the scope of this series.) As far as McDougall is concerned, the Manitoba experiment holds promise and a version of it might work in Cape Breton, but the Nova Scotia Office of Immigration has to “be ready to fight for it, too.”